The Loss Of The S.S Trevessa

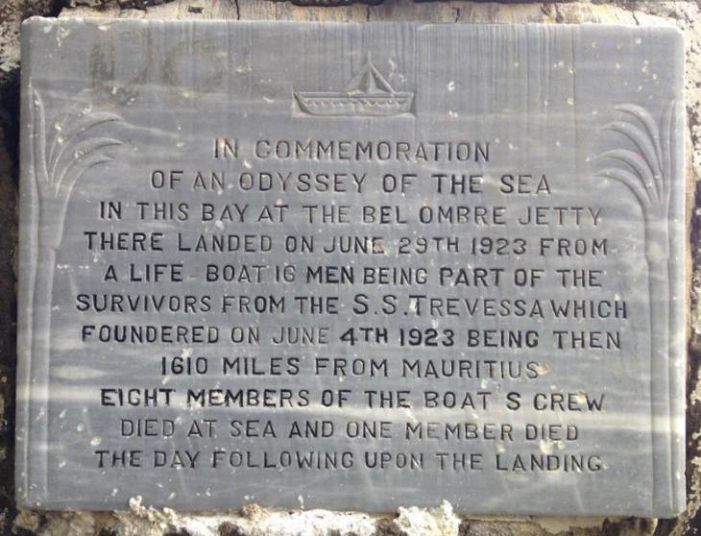

On the 7th of December, 1923, on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, there took place the final of a series of Board of Trade meetings, which then issued its Wreck Report for the steamship Trevessa. This report described the events leading up to the sinking of this ship, belonging to the well-known shipping company Hain, of St Ives in Cornwall, and what happened afterwards. It took place in Mauritius because it was on this island, and its neighbour Rodriguez Island that the two open lifeboats of the Trevessa had arrived after over three weeks of an astonishing voyage of 1728 miles across a large part of the Indian Ocean after their ship sank, and it was generally believed that they had been lost.

Once the news of the voyage and that 34 out of a crew of 44 had survived was heard, it became international news, with headlines around the world. The survivors were brought home and Captain Cecil Foster in particular became a great celebrity. He was summoned to an audience with George V and was impressed with the King’s practical knowledge of seamanship and navigation. He received many gifts including the Lloyd’s Silver Medal for Saving Life at Sea, also awarded to his First Officer. In 1924 Foster wrote a book about the adventure, using the short notes he and the First Officer had managed to keep in such difficult conditions and it rapidly became a best seller.

Foster had been at sea since he was 12 and was only 33 at the time, a young captain, but was modest and much of his short book praises the conduct of the crew. In his book he said that he had never given up hope and that the crew in his own boat were a ‘wonderful crowd’ only too willing to trust him. This is an understatement as it is so clear that their trust was entirely appropriate.

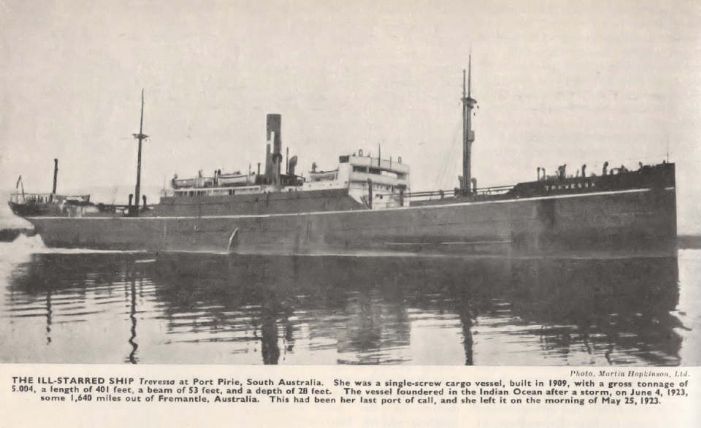

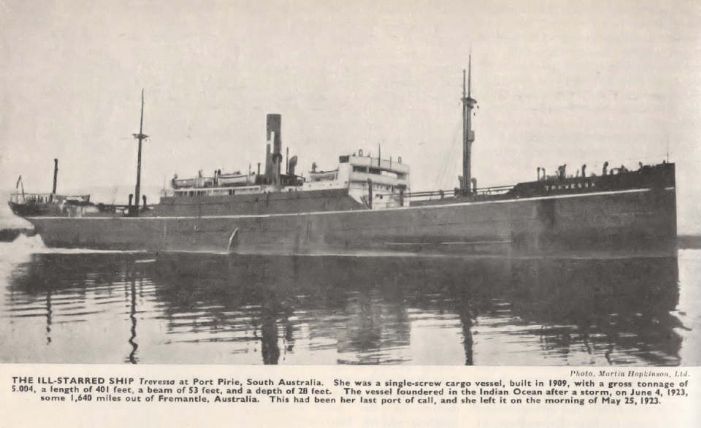

The sinking of the Trevessa could not be blamed on any individual. Hain’s ships, and those from other companies, had for some time carried cargos of zinc concentrates from south Australia to many world destinations and the general practice was to pack oakum into any cracks or crevices below the bulk concentrate so that water would not get into the bilges, even if it could soak through the bulk zinc, which was unlikely, as it had been poured into the ship’s holds and was fairly solid. There had been no notable disasters using this method. However, leaving Australia, the Trevessa ran into heavy gales, with many big seas crashing over her decks, eventually damaging two out of the four wooden lifeboats. On the night of June 3rd, the ship was hove-to in big seas and water was heard swishing about in the forward hold but when the pumps were put on, there was no water below the tanks to be pumped but water was pouring in through the bulkhead. It became obvious that the ship was tipping down by the head and at 0100, Foster ordered an SOS sent, and told the crew to abandon ship, using the two undamaged starboard lifeboats. It was a black night, a strong wind and very heavy seas of 20 to 30 feet so it was far from easy to drop the boats and get the crew and their lifebelts into them. There was very little time.

It was now that Foster’s experience and decision-making proved life saving. The traditional food to put into lifeboats for emergencies had always included quantities of tinned meat, but Foster had already been in a dangerous lifeboat situation during the first world war and had decided from this experience that salted meat was useless. He had previously trained the Chief Steward so that he and the other stewards immediately went aft, hauled boxes of biscuits and condensed milk up perpendicular ladders and struggled back with them on the tilting deck, through storm waves washing over them, to divide them between the two lifeboats. These already had stores of water, and some biscuits and some tobacco and cigarettes were quickly found to add to them. There was no time for a second trip. In the final minutes, Foster had got to the bridge, measured the distance to the nearest land on the chart, and then sent the chart and sextants to the boats, then following himself. With a huge effort the crew used oars to get clear of the sinking ship and watched the Trevessa disappear, head down, with her lights on.

The two boats were identical but the single sail on the Captain’s boat was a little larger than that in the First Officer’s boat making the former faster in a good wind although even a good wind provided only a few miles an hour. At first they stayed together, with 20 in the Captain’s boat and 24 in the other, but, having agreed to make for Mauritius, using the wind behind them and a westerly current, they parted, the Captain’s faster boat going on ahead. Reading Captain Foster’s small book is a revelation. He had little paper or cardboard on which to write, and it was almost impossible to keep anything dry. His crew included some east Asians, men from the Bristol Channel and West Cornwall region and ranged in age from 19 or younger, to 62. He quickly divided them into their familiar ‘watches’, with different tasks when not sleeping, such as baling out, rowing (if seas calm enough), managing the sail, doing repairs and watching out for other ships. Tobacco became a reward for a period of work done and food and drink were shared out at fixed intervals, in such a way that all could see that shares were exactly equal. There is no doubt that this prompt resumption of ‘normality’ was a strong factor in keeping up the morale of the crew and their willingness to obey the Captain.

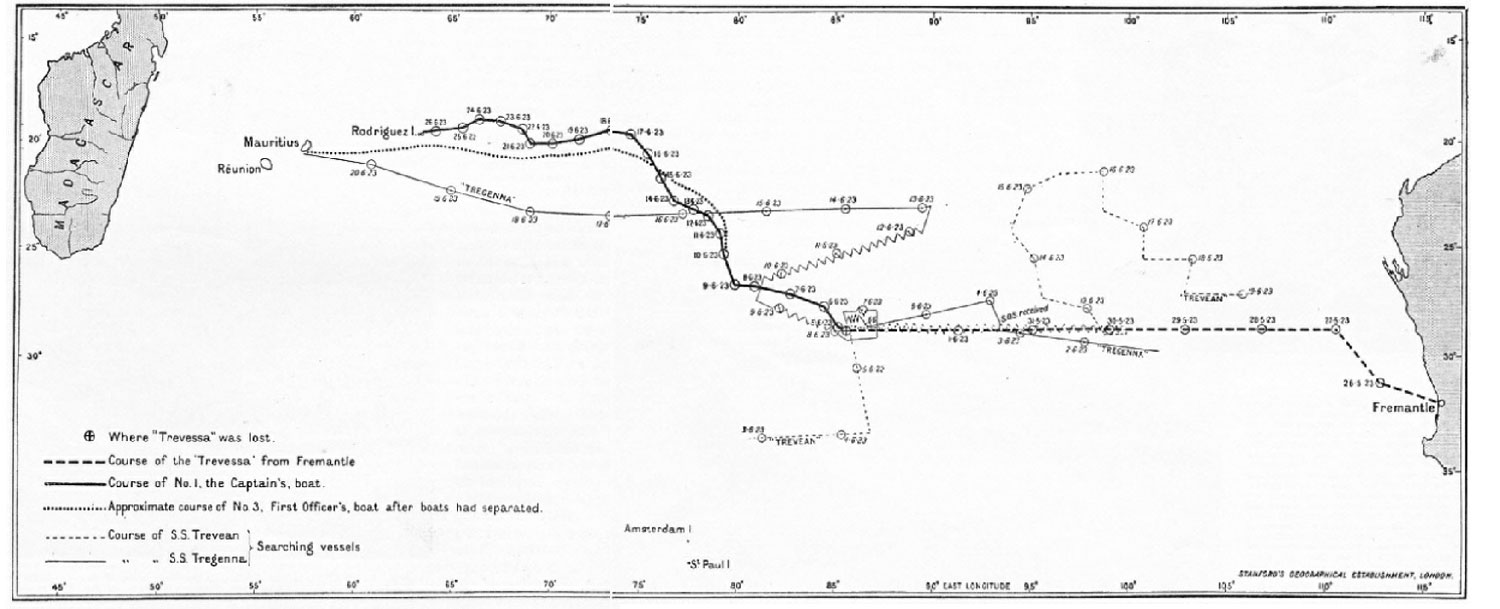

A GALLANT FIGHT FOR LIFE was made by the members of the S.S. Trevessa, and the courses their tiny boats took are shown on these maps. No. 1 Boat travelled 1,556 miles to reach Rodriguez Island, and No. 3 Boat 1,747 miles to Mauritius. No. 1 Boat’s voyage occupied twenty-two days nineteen hours, and No. 3 Boat’s voyage took twenty-four days twenty hours. The number of men lost after the Trevessa had been abandoned was eleven, most of whom died of exposure and exhaustion. It was decided to separate when the lifeboats had been six days together so that their chances of being seen and picked up might be doubled. In the event of one being rescued, help for the other boat might be sent in the right direction.

He had no books, charts or chronometer in his boat – they had gone to the First Officer’s boat; all he could do was calculate latitude when weather permitted, and having looked up the latitude of Mauritius before abandoning ship, he had to get the boat to that latitude as soon as possible and then head west, using the sun and stars to navigate. The Captain took care to nod and smile to himself as he noted each day’s reading, reassuring all the anxious faces watching him that all was well and they were on course. He also taught one or two others how to navigate like this, in case he did not survive himself.

Apart from the great need for water, helped very occasionally by rain and the various ways which the crew invented in order to catch some, the main problem they all faced was the overcrowding. Men and stores were packed in tightly, with many seasick or becoming delirious. To lie down to sleep was very difficult and to move around at all was almost impossible, for example to haul the sail up or down, to open store boxes or do repairs and by the end, most had hugely swollen feet and had virtually lost the use of their legs. The frequently wet and windy weather made everyone constantly cold. Two men died and were buried at sea. However, the boat did not miss its destination, finding at last on June 26th the tiny island of Rodriguez where they were greeted with astonishment and well looked after, before being sent home. Four days later, the First Officer’s boat arrived at Mauritius.

The Captain’s boat itself was sent to an exhibition in London, being used as a collecting point for the RNLI. It then appeared on Hove sea front for several years, but has now vanished, the site of its display being covered by the new Leisure Centre. Mauritius remembers the men of Trevessa at an annual Day of the Seafarer every June. The grave of Captain Foster can be found at Barry, and a display of the Hain Steamship Company’s ships is in the St Ives Museum. At Lelant church, there is a memorial and window to the young apprentice Harry Sparks, who was sadly one of the few who did not survive the long voyage in an open boat.

Highly recommended is Captain Foster’s own book The Loss of the Trevessa, a second edition of which is in the Morrab Library, Penzance.

Note: the is a bit of a mystery about the Trevessa in so far as the website Tyne Built Ships says she was built by Redheads in 1899 and was sold by Hains in 1920 and renamed Miramar, wrecked in a storm in Valpariso in 1926. The Shipwrecks of Mauritius Blog has Trevessa as a Turm Hansa class cargo vessel built in Flensburg in 1909, though it does record the correct date for the wreck and the correct captain and owner. Wrecksite.eu agrees with the Flensburg construction and adds that Trevessa had been originally named SS Imkenturm and was ceded to Britain after WW1 when she was acquired by Hains. It seems likely that the original Trevessa was sold and replaced by the Imkenturm which was renamed Trevessa and thus became a rarity in the Hain fleet in that she was not built by Redheads.